Land taxation should replace all other forms of state taxation. For the reasons that I will describe below many economists, tax theorists, politicians, and philosophers have strongly advocated for land taxation to be the dominant or sole source of taxation. Adam Smith, Henry George, Alfred Marshall, Paul Samuelson, Milton Friedman, Michael Hudson, Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, Thomas Paine, Aristotle, Plato, Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Thomas Spence, and Francois Quesnay are just a few.

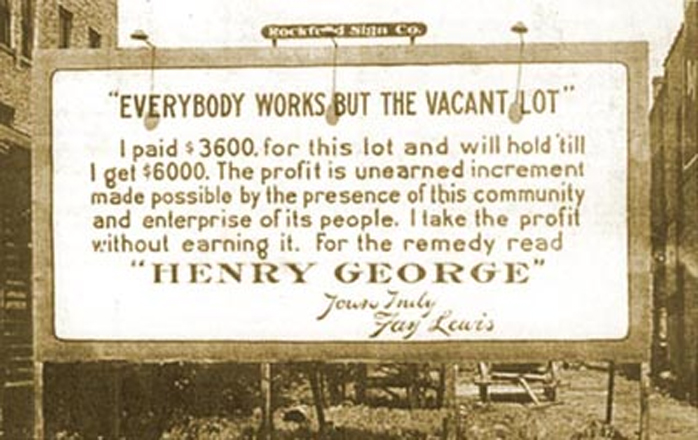

Land taxation has been popular among economists throughout history. Many of them believed that that taxing land and housing, rather than income is the key to a fairer economy. Henry George, one of the most famous tax theorists in history, argued that land-value levies should replace all other taxation, leaving labor and capital to flourish freely, and thus ending unemployment, poverty, inflation and inequality. George argued that when the site or location value of land was improved by public works, its economic rent was the most logical source of public revenue. [1]

Adam Smith said “nothing could be more reasonable”; Milton Friedman termed it “the least bad tax”. Winston Churchill said scornfully that a landlord “contributes nothing to the process from which his own enrichment is derived”. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based think tank for industrialized countries, supports the idea. So too did a recent working paper by the International Monetary Fund and the Mirrlees Review of British taxation by the Institute of Fiscal Studies. The mayor of New York City, Bill de Blasio, hopes that taxing vacant lots by value will help deal with urban blight in the Bronx and elsewhere. [2]

Benefits

The reasons commonly cited by proponents of governments deriving most or all of their taxes from land include:

1. Encourages economic activity. Not taxing income and profits encourages workers to work, which will have the net effect of increasing middle class spending, creating a virtuous cycle of economic activity.

2. Encourages the growth of a strong middle class. People in the lower class are working paycheck to paycheck, trying to make ends meet.

3. Encourages upward mobility. No state tax on employment income would help the lower class grow into the middle class strata.

4. It is more equitable. The wealthy pay a greater share. Wealthy people tend to own more land, poor people very little. Therefore taxing real estate is effectively a progressive tax (the poor pay less, the wealthy pay more, poor). Thus it would be paid for by those with a higher ability to pay, and reduce the tax burden of lower income families. Land value capture would reduce economic inequality, increase wages, remove incentives to misuse real estate, and reduce the vulnerability that economies face from credit and property bubbles.[3]The tax burden would fall on land owners and cannot be passed on as higher costs or lower wages to tenants, consumers, or laborers.

5. Encourages the productive use of land. Under a land-based taxation system land hoarders are penalized and, since the tax increases the total cost of land ownership, owners are encouraged to put the land to its most productive use. Land hoarding is quite a big concern in post-industrial cities like Detroit, Toronto, and Pittsburgh.

Photo: Detroit, Michigan

6. Discourages urban sprawl. Taxing land increases the overall cost of land ownership. Increasing total cost of ownership will encourage owner to develop their land upward and not outward. It’s quite clear that this would be the result as cities where land is expensive tend to grow upward (ex. New York, San Francisco, Tokyo, etc).

7. Less costly to enforce. Taxation on profits is costly to enforce. In comparison, land-based taxation is easy to enforce. If the owner doesn’t pay, the land can be easily seized and sold and taxes can’t be avoided by moving the land to the Bahamas or Luxenburg.

8. No Loopholes. Taxation of income and profits not only discourage economic activity, but it also displaces it. In order to pay less tax, companies relocate or exploit loopholes. The tax code is so porous that companies and creative accountants can choose from several means of escape. The growth of tax inversions is one such example. A tax inversion is when a company changes its country of incorporation to avoid taxation without changing its majority ownership, management, or headquarters. See Bloomberg’s list of company tax inversions, a list of over 50 large corporations who have completed inversions to avoid taxation.

Example:

Texas. A majority of states finance state and local government through some mixture of sales taxes, property taxes and income taxes. Texas is one of nine states that do not have an individual income tax. Even with regard to property tax, Texas does not have a statewide property tax. Property taxes differ from county to county. Governor Rick Perry touted Texas’ low taxes, and its lack of an income tax in particular, for the reason that an estimated 1,000 residents were moving to Texas every day, a trend often referred to as the “Texas miracle.” High-ranking officials in Georgia, North Carolina and Ohio have also cited Texas in recent months as a model for tax reform. [4]

Challenges

More than 30 countries have some form of land taxation, but this form of taxation isn’t free of difficulties. The three often cited difficulties with this form of taxation include:

1. Changing behavior. Land taxation invokes furious opposition from landowners, who see it as unfair. The landowning lobby is strong. A significant percentage of landowners believe that since they worked hard to acquire and develop land, they are entitled to its benefits.

2. Balancing winners and losers. Some entities control significant land, and it is in the public’s best interest for them to do so, but they would not have the means to pay (ex. golf courses, urban car dealerships, urban landowners with gardens). For this reason, exceptions to the tax would have to be developed to encourage certain uses that the society deems important (ex. urban gardens).

3. Assessments of high-priced urban land. Wealthy landlords could find ways to tie up assessments with costly legal knots to delay and fight the taxes levied.

Though it appears that economists, politicians, and philosophers throughout history strongly have favored land-based taxation, the landowner lobby in the United States is strong. Though there are clear benefits of land-based taxation, it is unclear whether these benefits will actually materialize in practice. The answer may lie in the details and specifically how this taxation structure is implemented. Due to the nature of our politic system and politicians’ preference for short-term small benefits over than long-term large impacts, it is unlikely that any politicians will risk taking on the landowning lobby, even if the new system is clear more fair and equitable.

Citations:

- George, Henry (1879). Progress and Poverty. The often cited passage is titled “The unbound Savannah.”

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_value_tax#cite_note-McCluskey_and_Franzsen-37

- Land Value Taxation: An Applied Analysis, William J. McCluskey, Riël C. D. Franzsen

- http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/24/us/in-texas-the-joys-of-no-income-tax-the-agonies-of-the-other-kinds.html?_r=1

Leave A Comment